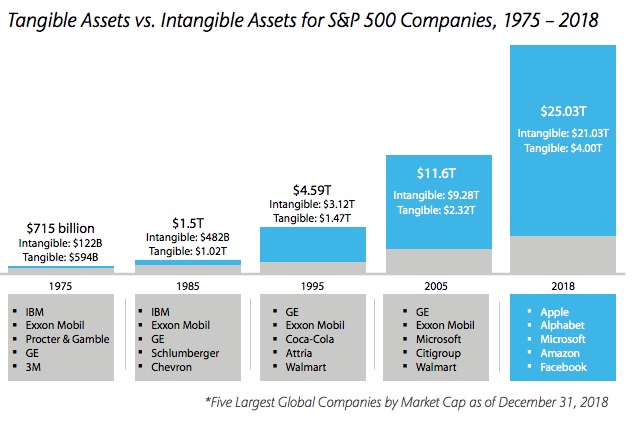

Over the past 20 years, intangible assets have become the dominant factor in company valuations. Today approximately 85% of the valuation of the S&P 500 is defined by intangibles, while in 1975, that percentage was just 17%. Intangibles are notoriously difficult to value. Given their slippery nature and their power to generate returns, it’s worth paying attention to the qualities of intangibles. How did they become so powerful? Let’s take a closer look.

When it all started

Intangible assets took off in the 90s as global commerce and brand recognition became focal points. Then the dotcom era boom and bust 20 years ago accelerated the power of intangible assets. As the digital revolution took hold, many companies with no revenue and no products raised large amounts of money in anticipation of ‘something’ happening. This hype led to a significant miscalculation of company valuations, mostly based on intangibles.

Value creation reports

Professor Baruch Lev of NYU’s accounting department has written for years that accounting standards have not addressed the intangible valuation. He published a book on the subject in 2016 called “The End of Accounting.” He suggests that a “value creation” report would be far more valuable than the standard financial statements used today.

Tangible assets are straightforward: cash, land, equipment, inventory, bonds, etc. Tangible assets are also easy to value, insure and have efficient secondary markets to buy and sell.

Intangibles can be patents, intellectual property, B2B rights, brands, copyrights, trademarks, web domains, software licenses, data, non-revenue rights, relationships, customer lists, etc. These assets are more likely to be undervalued and underappreciated by the market because they are unique and conceptual. This meteoric rise in intangible values accounts for most of the market value growth over the last 20 years, as you can see in the picture from an intangibles report produced by Aon.

Power laws and the network effect

An excellent example of undervalued intangible assets was the rise of social media and the network effect. Metcalfe’s law states that the value of a network is proportional to the square of its users. Even if social media users had expanded linearly, their value would still have expanded exponentially. Facebook’s intangible value grew as its users grew and they solved their monetization question with an advertising engine. Google experiences this network effect when they monetize the 90% of global search traffic that they currently control. Google is mostly an intangible asset business with two billion lines of code.

The power of a company owning a verb or a noun

One of the most remarkable transformations in intangible value comes when a brand name becomes a household noun or verb. One historical example is “Band-Aid,” a brand name owned by JNJ for the last 100 years. No one calls it by its real name: adhesive bandage. No other company has the right to sell a “Band-Aid” other than JNJ.

More examples include: “Google it,” “Pdf it” (Adobe), “Take an Uber,” “Tinder-date,” “Schedule a Zoom,” “Send the Docusign,” “Venmo,” etc. DocuSign and Zoom experienced explosions in their intangible brand value this year, and their sales and valuations have exploded with it. It’s difficult to value a brand, but when you witness a brand become a verb or a noun, consider the immense impact that it’s had in the past.

Intangible monopolies

Adobe’s pdf product (portable document formula) created in 1993 is a great example of a monopoly. PDFs are the standard and Adobe owns the rights. The Nike swoosh is an identity. The Netflix ‘ta-dum’ is repeated so many times it is the most recognized sound in the world. These brand identities are unique and deeply entrenched in our daily lives, and no one else can use them.

Putting it all together

Clever people can easily abuse the power of intangible assets. WeWork and Nikola are two good examples. WeWork was the largest private company bust in history after they promised to be much more than a real estate company. They couldn’t escape from the tangible nature of their true business model.

The rise of the intangible market economy aligns with the trends that we’ve seen accelerate during covid. The inherent difficulty of valuing intangibles may help explain why some valuations seem so high and so disconnected from the rest of the economy. We don’t see this trend slowing down anytime soon. In fact we expect it to continue over this coming decade as companies compete for ongoing ground-breaking innovation, talent, software, and ultimately, sustaining customer appetite for those innovations.

Weekly Articles by Osbon Capital Management:

"*" indicates required fields