The Incredible Shrinking Market

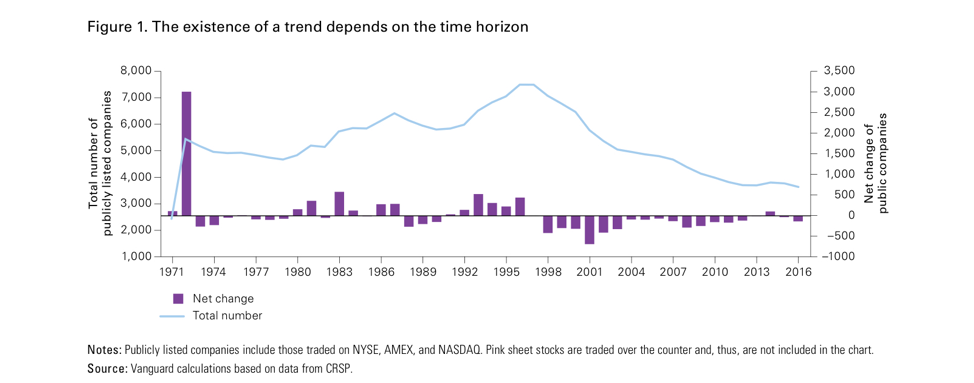

The New York Times published a feature article last week on our shrinking US stock market. It’s true that the number of publicly listed US securities has dropped from over 7,000 in 1996 to fewer than 3,800 today. That sounds like an economy that’s becoming less diverse, less innovative and less competitive. Is that really the case? Are these numbers a warning sign for investors? Let’s sort it out with some added context:

Microcaps make up most of the change

The 1990’s peak in the number of publicly traded companies was largely due to the surge of the internet and tech-related IPOs. From 1998 to 2002 we saw thousands of companies go public and thousands of companies de-list each year. With that much activity, we have to question if many of those companies should have been public in the first place. Many hot companies in that time frame are long gone.

Those missing microcaps ($150M or less) account for most of the decline in the total number of stocks. Microcaps peaked at 4,100 companies in the 90’s, falling to less than 1,500 today.

Our regular readers and clients know that we often use the size of a market as a heuristic to gauge its scope and relevance. So how large is the market for microcaps? It’s currently about .1% of the total US stock market, down from .2% in the 90’s. So the loss of 2,600 listed microcap companies, although it sounds huge, represents a very tiny impact on diversification.

Why the change?

Vanguard’s research on this subject indicates that today more companies are being acquired than going public. It makes sense. Why IPO at $200M when you can benefit from the expertise of joining forces with a company like Google or Facebook?

For investors, this actually makes it easier to diversify. Owning Google, Facebook or Amazon means owning many different business units in many different sectors, businesses that could stand on their own as public companies. The microcap diversity is still there but under the umbrella of larger entities.

Concentration is lower

Does the loss of so many companies mean the market is more concentrated? It may sound shocking to hear that the top 10 US public companies make up 23% of the total. But it’s less shocking when you learn that this is actually lower than it was in the 80’s when the ratio was 26%. The largest companies have always and will always represent a big chunk of the market.

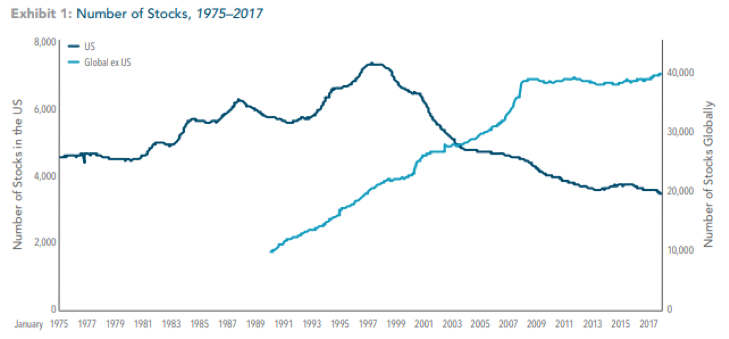

Non-US listings are booming

For those worried about reduced diversification, keep in mind that there’s much more to the market that US companies. This chart from DFA shows the boom in non-US listings from 20,000 to 40,000 (right side). Compare that to the drop in US listings (left side). There are far more companies trading worldwide than at the turn of century.

The V word

The New York Times story included an odd comparison that I’d like to clear up.

“There were 23 publicly listed companies for every million people in 1975, but only 11 in 2016, according to Professor René Stulz. This puts the United States ‘in bad company in terms of the percentage decrease in listings — just ahead of Venezuela,’ he said.”

The number of publicly listed securities per capita is a bizarre economic metric. I’m not sure it tells you much about the health of an economy. Furthermore, drawing a comparison to the humanitarian and economic crisis in Venezuela is misleading. Venezuela’s biggest problem isn’t its number of publicly listed securities per capita. Not even close! And the US is definitely not in a similar situation.

One of our missions at Osbon Capital is to continually promote transparency for investors. Unfortunately, financial media often obscure and dramatize market stories to generate controversy, attention, likes and shares. We feel it’s important to discuss stories like the shrinking stock market and put stories like these back into context so that investors have better information to make investment decisions. If you see a story that leaves you wondering, let us know.

Weekly Articles by Osbon Capital Management:

"*" indicates required fields