We’re at a crossroads for large technology monopolies and their platform business models. If we regulate them and slow their growth, they could stall and lose out on new opportunities. If we don’t regulate them, they could increasingly grow more dominant while crowding out new entrants and resting on their laurels. Competition is what keeps companies fit, lean and hungry. The regulators do not have an easy task ahead of them.

Tech monopolies

Good examples of platform monopolies right now are Google’s search ecosystem (information search), Facebook (people connections, news and information), Amazon (e-commerce) and Apple (iPhone, personal data, etc.)

Every other decade, it seems, federal regulators decide to take on the dominant corporation. Today, in Google’s case, prosecutors have to prove that Google holds not just a monopoly, but a harmful monopoly.

In the early 2000s, Microsoft was the target. In the 1980s, it was IBM. There’s no question that today’s big technology companies are dominant. Big tech can afford the best talent, borrow at the lowest rates, and they own vast, fully scaled digital ecosystems that are convenient, sticky and fully integrated into our daily lives.

What happens if we regulate?

During the industrial age, regulation became necessary when monopolies controlled the means of production and distribution. A good example is Standard Oil, which amassed control over 80% of the available oil and distribution. Regulation in the industrial age was much easier because a ‘thing or substance’ was being controlled. In the information age, intangible and highly profitable monopolies are difficult to define.

Regulators understand that the big US technology companies are responsible for most of the US’s economic growth for the past decade. Blunt and indiscriminate regulation of big tech would almost certainly slow or stop their growth. Considering that US big tech companies and Chinese big tech companies are fighting for global dominance, US regulators want US big tech to succeed. FTC commissioner Christine Wilson said in March, “no monopolist is truly safe; each one must keep innovating to preserve its dominance. When monopolists become complacent, they will fail.”

Dominant technology companies do not always stay dominant. IBM created a whole culture of programming, data collection, and speed that led many other companies to branch out independently. Similarly, Xerox, a copying company, and its Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) created the mouse, the graphical user interface, and the desktop computer later popularized by Apple and Microsoft. Many years later, Apple (devices) and Microsoft (cloud) are thought to have platform power because their products and services are not detachable. You can understand why the regulatory urge is starting again today, but you can also see how much worse we would have been had regulation started sooner.

Some argue that the US’s attempts to regulate Microsoft in the early 2000s resulted in a decade of lost opportunity and sub-par stock growth. Microsoft was initially given a breakup order in June of 2000. That order was subsequently reversed one year later. By the end of 2001, Microsoft agreed to a consent order not to engage in monopolistic practices with browsers for five years, which by this time was mostly meaningless. Microsoft could probably blame regulators for Internet Explorer losing out to Google Chrome as the top web browser.

What happens if we don’t regulate?

The only time that society suffers from no regulation is when the interests of the platform provider diverge from the interests of the user. Money and power alone are not enough to justify regulation. Even dominance is a questionable regulatory criterion when they are so many formidable competitors. Now that technology operates globally, possible dominance by Chinese companies in the United States should invite more attention to national security issues, not monopoly issues.

Regulation of monopolies can function as a kind of hidden tax. The monopoly pays the financial part of its share of the profits. Still, consumers may end up paying higher prices or may experience fewer choices and lags in innovative product releases.

Big tech is not the only tech and not the only opportunity

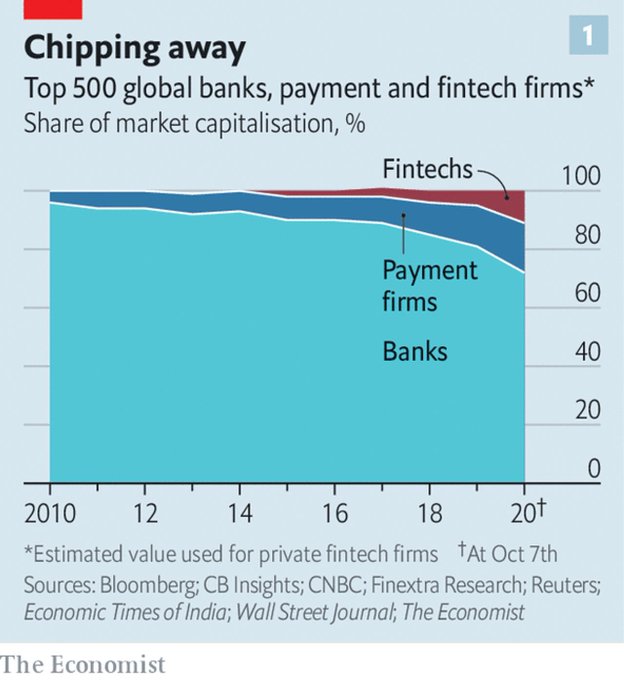

There are hundreds of mature, up and coming technology companies in the US and international markets. Technology-based business models are scalable, often high margin, can grow extremely fast and are intensely competitive. While the FANG stocks are the most dominant today, remember that these companies grew to behemoths in just 15 to 20 years. Paul Graham has said that Stripe (not yet public) reminds him of early Google days. It would be nice if Stripe were public as the digitization of finance is one of our top investment themes. It’s certainly possible that Stripe could grab a significant part of the light blue portion of this graph from The Economist.

We’ve written about the major investment themes a few times this year. It’s not possible to precisely predict what regulation will do to today’s most dominant technology companies. If Google started charging for search, you would change search engines immediately. In fact, most industries today are dominated by two or three major players that offer consumers a choice (including chemicals, credit cards, airlines, agriculture, telecoms, etc.). As long as at least two or three technology firms are competing, the consumer should be safe from monopolistic financial practices.

Weekly Articles by Osbon Capital Management:

"*" indicates required fields