Last week, the Biden Administration released its 2022 budget for the US Government. Along with many details about how the $6+ trillion budget is allocated, there is a table covering their assumptions including GDP growth and interest rate changes. Given the government has considerable controls to help turn these assumptions into reality, let’s take a closer look at our government’s projections over the coming decade.

The Biden Budget

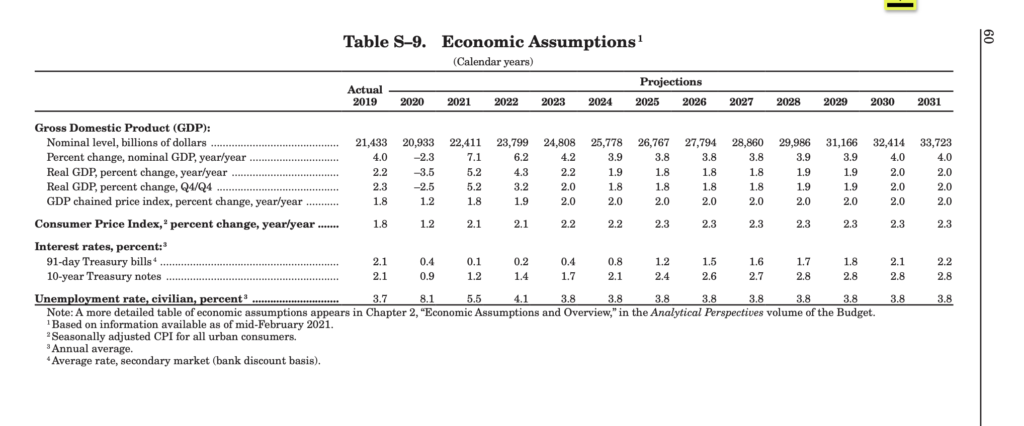

On page 60 of the Biden Budget, the administration lists their economic assumptions for the next 10 years. Here is an image of the page:

On GDP growth:

- The Biden Administration assumes that US GDP will grow from $22.4T today to $33.7T over the next 10 years. An expected increase of 50%.

- GDP grew from $15.285T to $22,061T over the past 10 years. That’s an increase of 44%.

GDP growth is directly related to the growth of the US stock market. If these assumptions come true, adding $10T to US GDP over the next 10 years would generate an attractive US stock market return from today’s levels with near certainty.

On interest rates:

- 91-day Treasury bills used to yield a juicy 2.4% as recently as just two years ago. This budget assumes we won’t hit that level even over the next 10 years. Two years ago, TBills were a really useful tool for cash management. It allowed anyone with cash to earn a guaranteed 2.4% return with daily liquidity. Today it’s not easy to find a yield on cash balances.

The majority of government bonds worldwide yield 0% or less. This page confirms that we can assume US government bonds will continue to yield less than 0% after you take the CPI (Consumer Price Index / one measure of inflation) into account. Government bonds are really not a rational investment unless you expect yields to drop even further below 0% to -2%.

Debt Levels

If you go deeper into the Analytical Perspectives behind these assumptions, you can learn more about how the US Government plans to address its debt levels. Essentially, rates must continue to stay low. As long as rates continue to stay in the low single digits, the US will be able to afford its debt.

US Government debt has increased 4x over the last 25 years, from $5T to $21T. Despite the dramatic increase, the cost of servicing that debt has not changed because rates have consistently decreased from nearly 8% in 1995 to roughly 1% today. Our government forecasts that we can double our current debt levels, to $40T, while keeping interest rate expenses limited to approximately 10% of the annual budget.

Understandably, debt makes people nervous. It’s really easy to write scary articles about debt, so we see a lot of them. Debt is also a useful tool for growth. Even though these debt numbers seem extremely large, they are mostly reasonable and affordable given persistently low-interest rates.

Sustaining growth

GDP growth requires two factors: population growth and productivity growth.

- We have twice the number of US workers today as we did 50 years ago, from 83 million to 160 million today. Our GDP per worker has doubled over the past 50 years as well. Population growth has been a significant contributor to GDP over the past century.

- It’s unlikely that we will double our number of workers over the next 50 years, from 160 million to 320 million, as population growth in developed nations has slowed considerably.

In order to hit our GDP growth targets, the US will likely have to focus more on productivity growth in terms of policy, taxes and subsidies. Productivity growth will have to come from innovative technologies that reduce friction to speed up commerce like payments technologies or increase output like robotic automations. Thankfully we are nowhere near maturity when it comes to unlocking the next wave of promising productivity-related technologies.

What happens if the US doesn’t hit these targets?

No previous version of the US Government economic assumption would have anticipated a pandemic or any other major crisis event. The Fed’s unexpected but swift response to COVID saved us from a multi-year economic depression.

Bloomberg columnist Matthew Boesler wrote a great column about future bailouts. He asked the question, “If you can replace 100% of the lost income in a crisis like this, why don’t we replace 100% of people’s lost income in every cyclical downturn?”

It’s a good question. But what do we consider to be a cyclical downturn? Is a cyclical downturn a stock market crash of 20% or 30%, a GDP decline (which lags by roughly three months) or an employment issue? Who gets to decide? Either way, I think everyone can agree that without the $12T+ in Covid related stimulus, the suffering would have been substantially worse.

Weekly Articles by Osbon Capital Management:

"*" indicates required fields