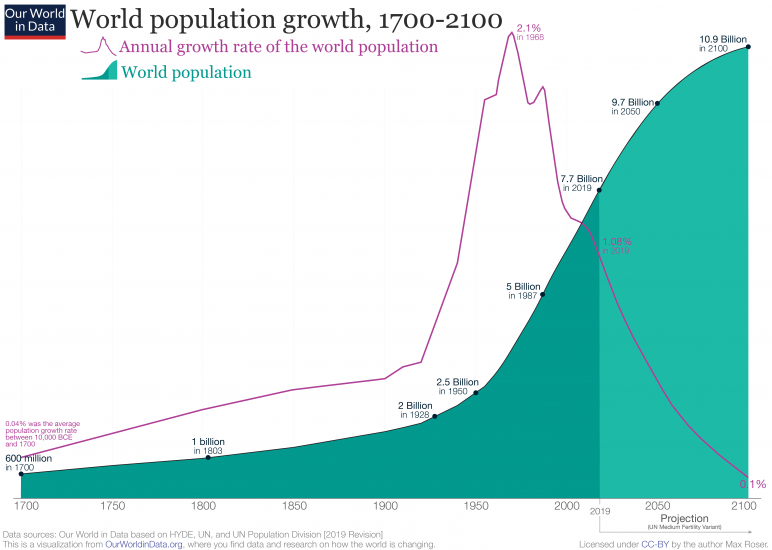

Population trends are often absent from investment research reports. Population growth rates are best when measured in decades and centuries, which is perhaps too slow to be considered new information. Since 1900, the world population has exploded from 1.6 billion to 6.1 billion in 2000 and 7.8 billion today. However, population growth passed an inflection point nearly 50 years ago and is now firmly in a deceleration phase. Here is what we know and what we can expect going forward:

Rates of Change

The world population grew 281% from 1900 to 2000 (1.6 billion to 6.1 billion). If that pace were to continue linearly (it isn’t and it won’t), we would hit 23.25 billion by 2100. The real estimate for 2100 is closer to 11 billion. That’s just 41% over the next 80 years – a staggering reduction in the growth rate.

Consider the impact on economics over the next 100 years. More people means more users, tenants, consumers, participants, etc. Will GDP expand on a regular annual basis after 2100 if the population doesn’t grow? GDP growth after 2100 will likely have to rely entirely on productivity growth and financial engineering. Since we live in a finite world, there’s a fundamental mismatch between our collective goal of infinite growth and nature’s constraints.

Infinite growth on a finite planet

Our governments and economic systems operate on the promise of continuous economic growth. At current production and consumption levels, we need 1.6x earths to support 7.8 billion humans. The mismatch between consumption and resources is known as ecological overshoot.

To have a sustainable society:

- We can’t draw down renewable resources faster than they regenerate (fresh water, lumber, fishing, etc.)

- We also can’t generate waste faster than it is rendered harmless (Co2, groundwater pollution, plastics, etc.)

- We can’t have any dependence whatsoever on finite resources for obvious reasons (fossil fuels, etc.)

Unfortunately, we fail at all three of the above, particularly within the developed nations. We passed this barrier back in the 1970s, right around when our population growth rate peaked. Our desire to continuously increase consumption, sales and economic gains is directly at odds with our ecological constraints. The evidence for this ecological mismatch is increasingly obvious.

Economic growth as a function of population growth and productivity growth

Jeremy Grantham, who manages over $100 billion at GMO based in Boston, has often said that economic growth is a function of population growth and productivity growth. Mr. Grantham has been vocal over the past decade about his dismal views of future global economic growth. Many people label him as a “perma-bear” and someone who is unnecessarily pessimistic.

If you follow his interviews, he often points to issues with population growth and productivity growth. We know that population growth is firmly in a deceleration phase. However, we don’t know what will happen next with productivity growth. We have some clues that productivity could increase exponentially as advancements like AI mature and scale.

Productivity growth and technology

We recommend looking at investments today through this lens of how it contributes to future productivity and efficiency. Cloud computing from Amazon, Microsoft and Google has given entrepreneurs the ability to create highly efficient and profitable SaaS business models. Warehouse technology and manufacturing robotics have replaced many mundane and repetitive jobs. It’s a challenge to find new jobs for those in the short run, but we’ve dealt with it many times. We used to pay telephone and elevator operators, for example.

Considering the pressures of overpopulation, companies that make us more productive are worth increasingly more on a relative basis. As the world population approaches its peak, we’ll probably need more sophisticated ‘robots’ to support future growth. AI is one of our best answers to date to this question. To implement AI into cars, computers, cell phones, etc., we need more GPUs from companies like AMD and NVDA, semiconductors from companies like TSM, the list goes on. Training an AI model at Google in the US costs $.49/hr. Eventually, we may view this cost as comparable to the cost of hiring an employee.

Financial engineering

There is a third lever that we haven’t addressed yet. Our governments manufacture economic growth by cutting interest rates and printing money. Money is an abundant resource today, and therefore cheap to borrow. Infinite money printing has the potential to ruin a currency, as it has many times over the course of history. I don’t believe that it’s a wise time to invest in companies that required a bailout this year to stay afloat.

My suggestion is to look past all of the financial engineering and look into the industry trends where businesses are most likely to succeed over the coming years. We outlined these in an article two weeks ago called: Major Themes and Investment Opportunities Over The Next Five Years.

Swimming with the tide

Awareness of the trends that are happening today can be quite valuable. Overpopulation, environmental issues and slow growth are issues that exist today. As population growth tapers off, companies that can increase productivity by cutting costs, reducing friction, reducing frustration, saving time and increasing output will become increasingly more valuable. The last 100 years of growth included tremendous population growth. Now that population growth is tapering off, investors should be increasingly selective about aligning their investments to the major trends.

Weekly Articles by Osbon Capital Management:

"*" indicates required fields